Latest posts View all

- The Early Palaiologan Aristocracy and the Common Good in Fourteenth-Century Byzantine History-WritingJames Cogbill With notable exceptions, studies of the political culture of the Byzantine Empire during the early Palaiologan period (c. 1258-1341) tend to privilege the… Read more: The Early Palaiologan Aristocracy and the Common Good in Fourteenth-Century Byzantine History-Writing

Resources

The ‘Common Good’ in Byzantium

Jean-Claude Cheynet

In our first Webinar in September, we saw that all regimes find their legitimacy for two fundamental reasons: to ensure the security of their subjects and to guarantee justice between them and their subjects, as well as between the subjects themselves. Security is ensured by the army and by diplomacy, both of which require financial resources, the origin of which is a subject of discussion, even litigation. Justice is much harder to define. It is manifested by respect for the law, it is still necessary that it be felt to be just.

But the feeling of justice includes many other much more subjective aspects, such as the rewards offered by the sovereign to his loyal servants without showing favoritism. These may be deemed insufficient or, on the contrary, reveal a favoritism deemed excessive in favor of his parents. Likewise, the ruler can be accused of unjust behavior if he too easily listens to accusations of embezzlement or dissent, or even if he falls into “tyranny” through arbitrary and malevolent acts.

Byzantine sources are poor in ‘mirrors for princes’ which describe “good government”, but emperors also sometimes gave advice to their successors. Imperial eulogies often describe emperors more as they should be rather than their actual qualities, but these are not works of pure fiction. Finally, the speeches attributed to the rebels against the imperial authority are sometimes integrated by the chroniclers into their accounts of the great rebellions. Obviously, these are not the speeches that the interested parties were able to pronounce, but those that the chroniclers wrote. These speeches nevertheless represent a supposed point of view of the protagonists of the rebellion. My paper will outline these sources, and in doing so, seek to establish concepts of the ‘common good’ in Byzantium.

People

Jean-Claude Cheynet

Jean-Claude Cheynet is emeritus professor of Byzantine history and honorary member of the Institut universitaire de France (2008-2013). A former researcher at the French CNRS (1977-1995), he is also a member of the Academia Europaea. He edited the Revue des études byzantines from 1996 to 2005 and co-edited the Studies in Sigillography from 2003 to 2016. He studies mainly the political, military and administrative role of the Byzantine aristocracy, which was the backbone of the state under the Macedonians and the Komnenoi (Pouvoir et contestations à Byzance (963-1210), Paris 1990; The Byzantine Aristocracy and its Military Function, Aldershot 2006). His other research area is on lead seals (La société byzantine. L’apport des sceaux, Paris 2008) and the edition with a commentary of lead seals catalogues (The last ones are: Les sceaux byzantins de la collection Yavuz Tatış, Izmir 2019); Les sceaux byzantins de la collection Savvas Kofopoulos, Tome 1, Paris 2022.

James Cogbill

James Cogbill is a doctoral candidate in History at Worcester College, Oxford. His research explores the mutually-inscribing interconnectivity of the premodern ruling family and ‘political culture’ – the framework of structures, practices and expectations within which political actors operated, and by which they were constrained – in the late medieval Byzantine Empire.

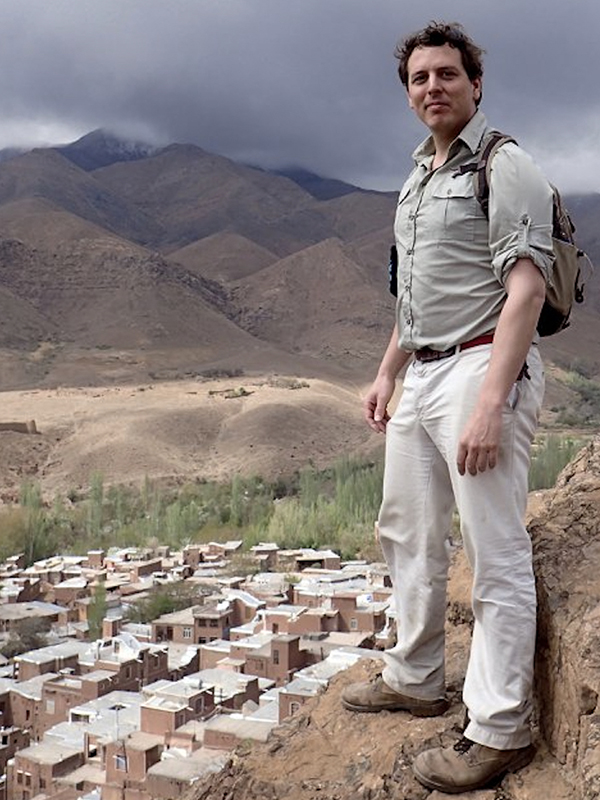

Maximilian Lau

Maximilian Lau is a Junior Research Fellow at Worcester College, Oxford, and a member of St Cross College, having previously been an adjunct professor of economic history at Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo. He wrote his doctorate on twelfth-century Byzantium and the Crusades, for which he carried out extensive fieldwork in the Balkans and the Middle East. He has published articles and book chapters on subjects such as Islamic warrior women, Armenian prophecy, Turkish civil wars, the Byzantine Navy and Middle Eastern influences upon Frank Herbert’s Dune. His monograph on the Byzantine Emperor John II Komnenos (1118-1143) will be published in 2023.